Rooted in Tradition: The Story of Big Cussetah’s Wild Onion Dinner

By Cynthia Mendoza-Aguilar

Big Cuseetah Methodist Church, Tarpaleche sisters. Cynthia Mendoza-Aguilar

MUSCOGEE, OK — The smell of wild onions clung to the aprons of the women moving behind long folding tables, their feet stepping gently on ground walked by generations before them.

Wild onion dinners aren’t just about tradition, they’re about staying rooted. In community, in memory, in love. The scent of onions lingers long after the meal, just like the voices, the stories, the care packed into every leftover plate. This isn’t just food, it’s identity, resistance, and celebration, served together, on purpose.

Clad in muted-yellow shirts with “Big Cussetah Bunch” printed across the front, the women moved with familiarity, laughter, and purpose, preparing to serve a crowd gathering outside, those who had lined up and paid $15 for a plate and a memory.

Every March, Big Cussetah United Methodist Church hosts its annual wild onion dinner, one of many held across the Muscogee Nation and beyond. These dinners are far more than fundraisers or meals; they are living ceremonies, deeply woven into the history and survival of the people.

Wild onion dinners bring together traditional foods that have withstood the test of time. Onions may be the opener, but they are not the only star of the show. Alongside bubbling pots of wild onions and eggs, guests find grape dumplings, sofki (a traditional corn drink with an acquired sour taste), frybread, macaroni and cheese, fried potatoes, ham, and salt meat dishes that tell a story far older than Oklahoma itself.

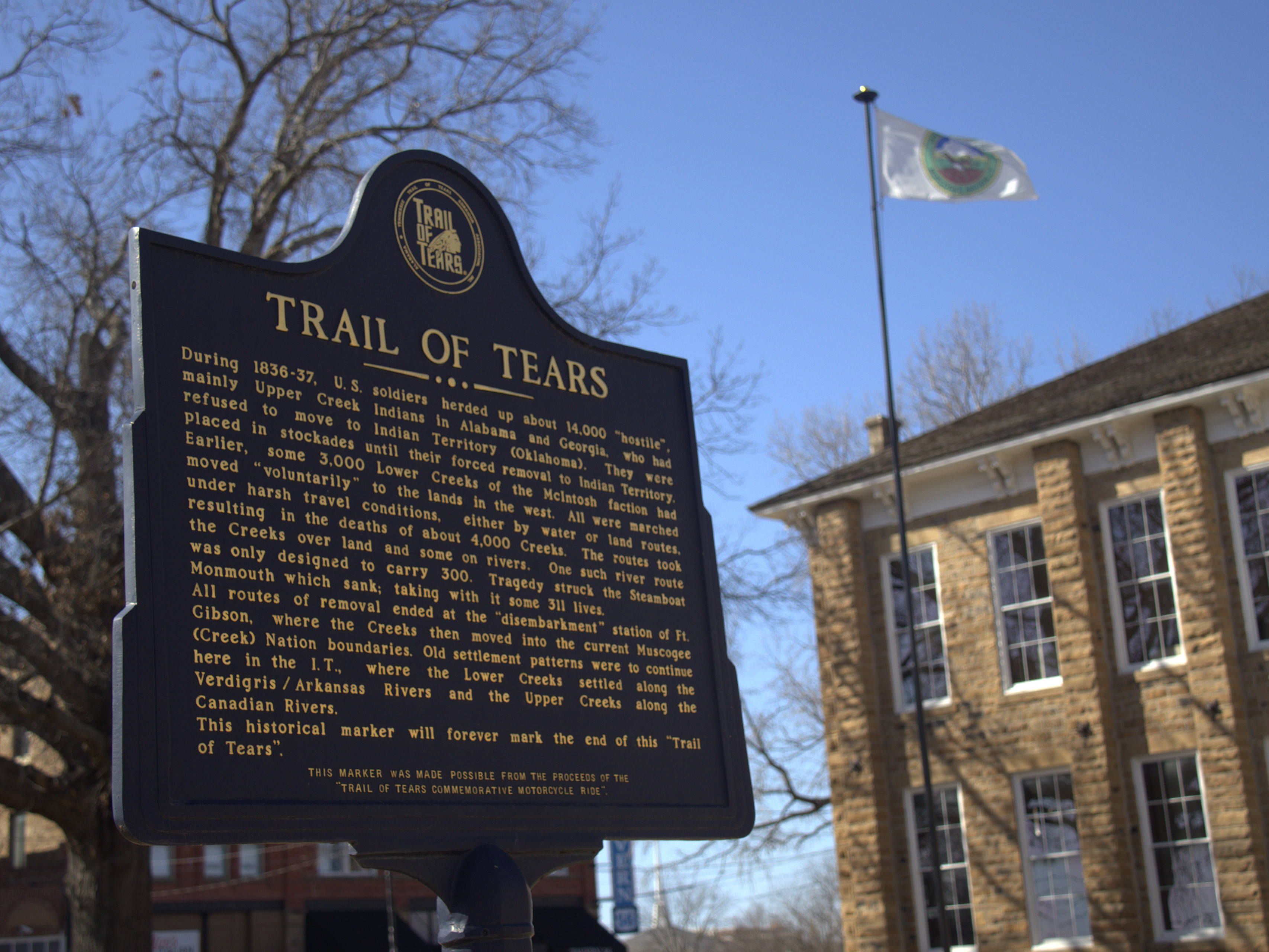

Harvesting wild onions has been a part of Muscogee culture since long before the Trail of Tears forcibly relocated tribes from Georgia and Alabama to Indian Territory in the 1830s: Cussetah, one of the relocated tribal towns, honors that heritage with each dinner. In the Muscogee language, March is “Tafvmpume Hompetv Hvse,” Eat Wild Onions Month, a time not just to harvest, but to gather, remember, and reconnect.

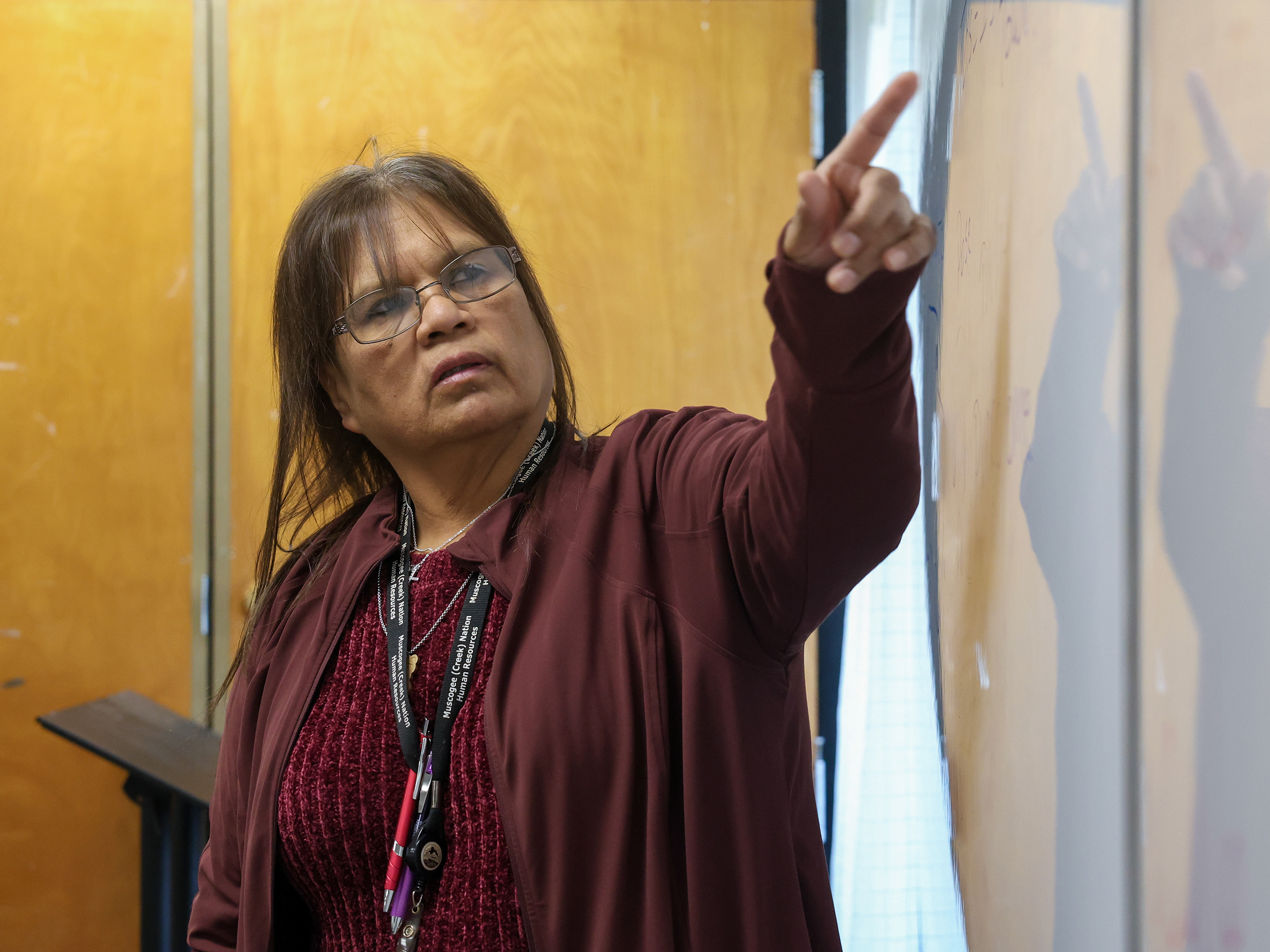

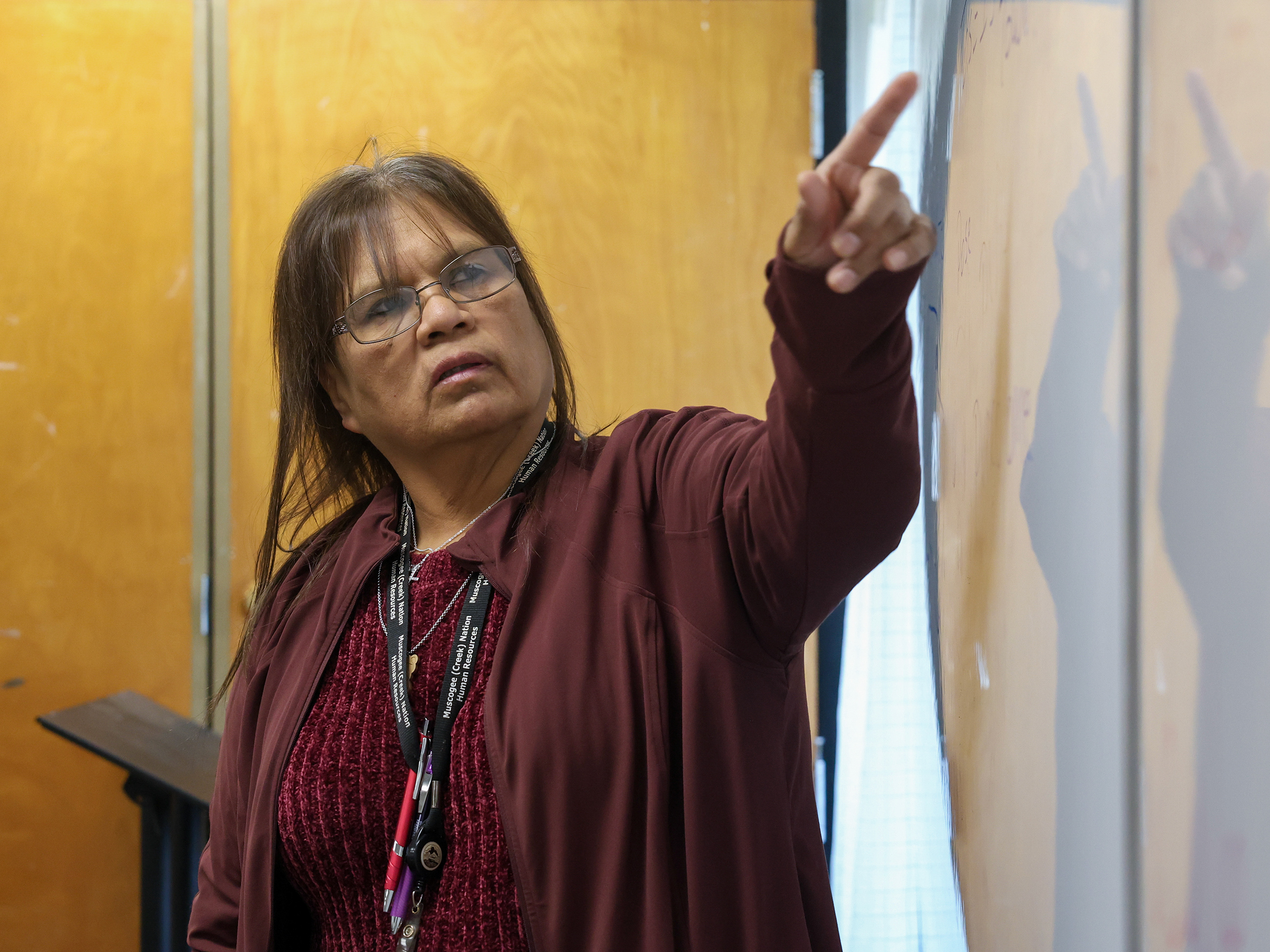

At Big Cussetah, the dinner involves everyone: children digging their hands into the soil to gather onions, women working together in the kitchen, and elders passing down recipes that have survived generations of upheaval and change. As Teresa Tarpaleche, one of the organizers, explained, "We just know it has to be done. It’s our home, and it makes you feel good."

For Teresa Tarpalechee, her sisters, and everyone else who grew up here, the dinner is a calling, not a chore. Every year, they prepare food for hundreds of guests, many driving in from Tulsa, Texas, and neighboring tribal towns. “By Saturday night, we’re going to be tired," Teresa laughed. "But it’s worth it. We’re doing it for the church.”

Yet even as the lines grow longer and the tables fill with laughter, many elders quietly worry about the future. “There’s not a lot of young people around anymore,” Teresa admitted. Some, like her son, have moved to cities like Broken Arrow or Tulsa, drawn by jobs, school, or new lives far from the small towns and church grounds where they grew up.

Photos of past generations line the walls of the dining hall, a reminder of those who came before, and a quiet question for the years ahead. The women preparing the meals know what’s at stake. “We took over what was taught to us,” said Diana Lynn Beasley. “Now we just hope the next ones take over, too.”

Despite the thinning numbers, the commitment remains. Nephews are learning how to cook pork. Little kids try to sneak pieces of salt meat off the tray. Elders share their memories, their recipes, their jokes, and their hopes, passing on not just how to make dinner, but why it matters.

The connection to the past is visible just outside the kitchen doors, where many of their loved ones rest in the church cemetery. “That’s where I'm going to be,” Teresa said softly as she giggled, not because she found it funny, but because what else is there to do other than laugh.

Each generation adds something new without letting go of what matters. Wayne Coaser, a member of the Cussetah Tribal Town and Fox Clan, recalled learning traditional ways or picking onions even when he didn't appreciate them as a boy. "Man, I hated it... I'm glad they showed us how, though," he said, smiling.

Recently, a shiny new turkey fryer was incorporated into the kitchen for cooking the salt meat, a modernization that didn’t erase tradition, but made it more sustainable. Ninety pounds of pork later, it wasn’t just about feeding the crowd; it was about being together, filling the air with familiar scents that echo across decades.

"Nothing’s more important than keeping our pride, keeping our heritage," said Christopher James Harjo, who learned to cook the pork butts over a pecan wood fire from his grandmother, Stella Haley Coser.

The line for food stretches long by 10 a.m., filled with locals, out-of-towners, members of other tribes, and first-timers drawn in by word of mouth. "Every year, without fail, we see someone new," Teresa said.

Visitors cross all walks of life. One man arrived to his first onion dinner wearing a "Make America Great Again" hat, and was welcomed without hesitation. "It’s not about politics," said Raelynn Butler, Muscogee Secretary of Culture and Humanities. "It’s about the will to have a good meal."

At Big Cussetah, food isn’t just nourishment, it’s memory, survival, and an act of quiet resistance. Every dish carries a story that predates Oklahoma, predates the church buildings, predates even the notion of a United States.

In the cemetery behind the church, the truth of the tradition becomes tangible. Wild onion dinners aren’t reenactments of the past; they are living practices. New tools enter the kitchen, young hands learn old techniques, and the fire of culture burns on, warm, open, and enduring.

Wild onion dinners root the Muscogee people in community, memory, and love. The scent of onions lingers long after the plates are cleared, like the voices and stories that refuse to be forgotten. Each plate is not just a meal, but a continuation, a quiet declaration that a people, and all they carry, still live.