Muscogee Musicians Preserve Indigenous Language Through Hymns

By Diego Hernandez

Elisa Harkins is a Cherokee and Muscogee Creek musician who preserves tribal languages through contemporary music and performance. Diego Hernandez

TULSA , OK — Before Elisa Harkins ever stepped onto a stage, she was in a small classroom learning hymns in a language she did not grow up speaking.

It began with a simple challenge. Her Muscogee language teacher, Don Tiger, asked her to learn a hymn and return the following week to sing it in front of the class. She had not been raised in a household where the language was spoken fluently, but she found a recording online, taught herself the words and stood up the next week to sing.

That moment marked a shift. It was the first time Harkins, who is Cherokee and Muscogee Creek, saw how music could be a bridge not only to language but to a deeper connection with identity and community.

“I was not really familiar with the hymns until I started going to language class,” Harkins said. “But when I started singing them, I realized how much of the language and worldview is embedded in the songs. That is what really pulled me in.”

Across the Muscogee Nation, hymn singing has long served as a cultural cornerstone, a tool of language transmission and a spiritual practice.

For elders like Pearl Thomas, who has spent decades leading hymns at Honey Creek United Methodist Church in Oklahoma, singing in Muscogee is not only a tradition. It is preservation.

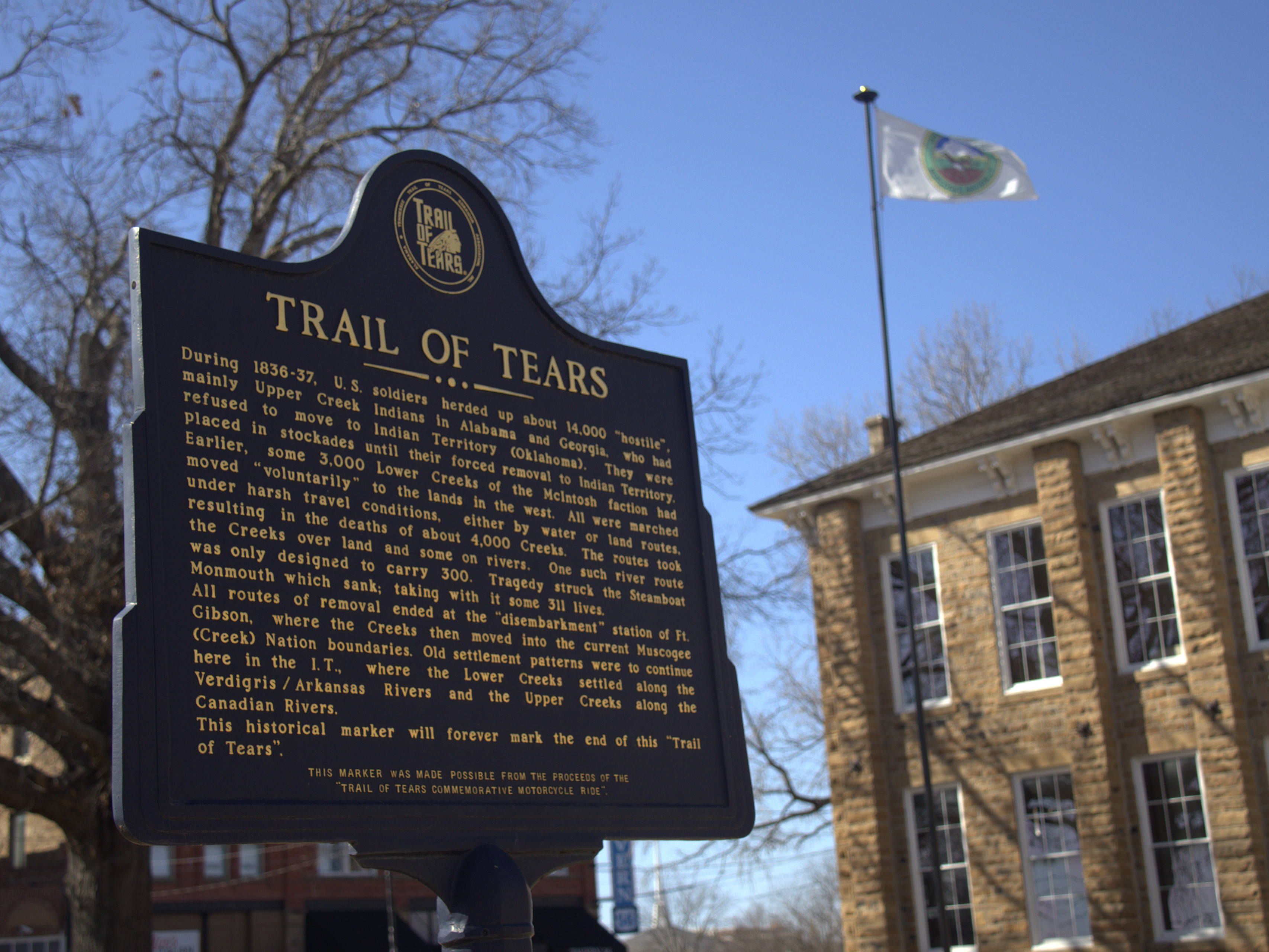

“These are songs that came with our people on the Trail of Tears,” Thomas said. “They sang to keep going. The hymns helped them survive.”

Many of the hymns sung today were first translated from English or composed by Muscogee speakers in the 19th century. They exist primarily in oral form, passed from one voice to the next, often without any written lyrics or notation.

That method of transmission, imperfect but deeply communal, has helped keep the language alive even in families where it is no longer spoken fluently.

“When we were growing up, there was no sheet music,” Thomas said. “You learned by listening. You sang until you knew it.”

The connection between hymn singing and language preservation occurs because the melody, rhythm and repetition make it easier to learn vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation.

For language learners of all ages, hymns can serve as a kind of auditory textbook, an emotionally charged and culturally specific curriculum.

For Harkins, hymns became more than a learning tool. They became a foundation for experimentation.

While studying electronic music at the California Institute of the Arts, she began translating her own original songs into Cherokee, becoming the first person to perform contemporary music in that language.

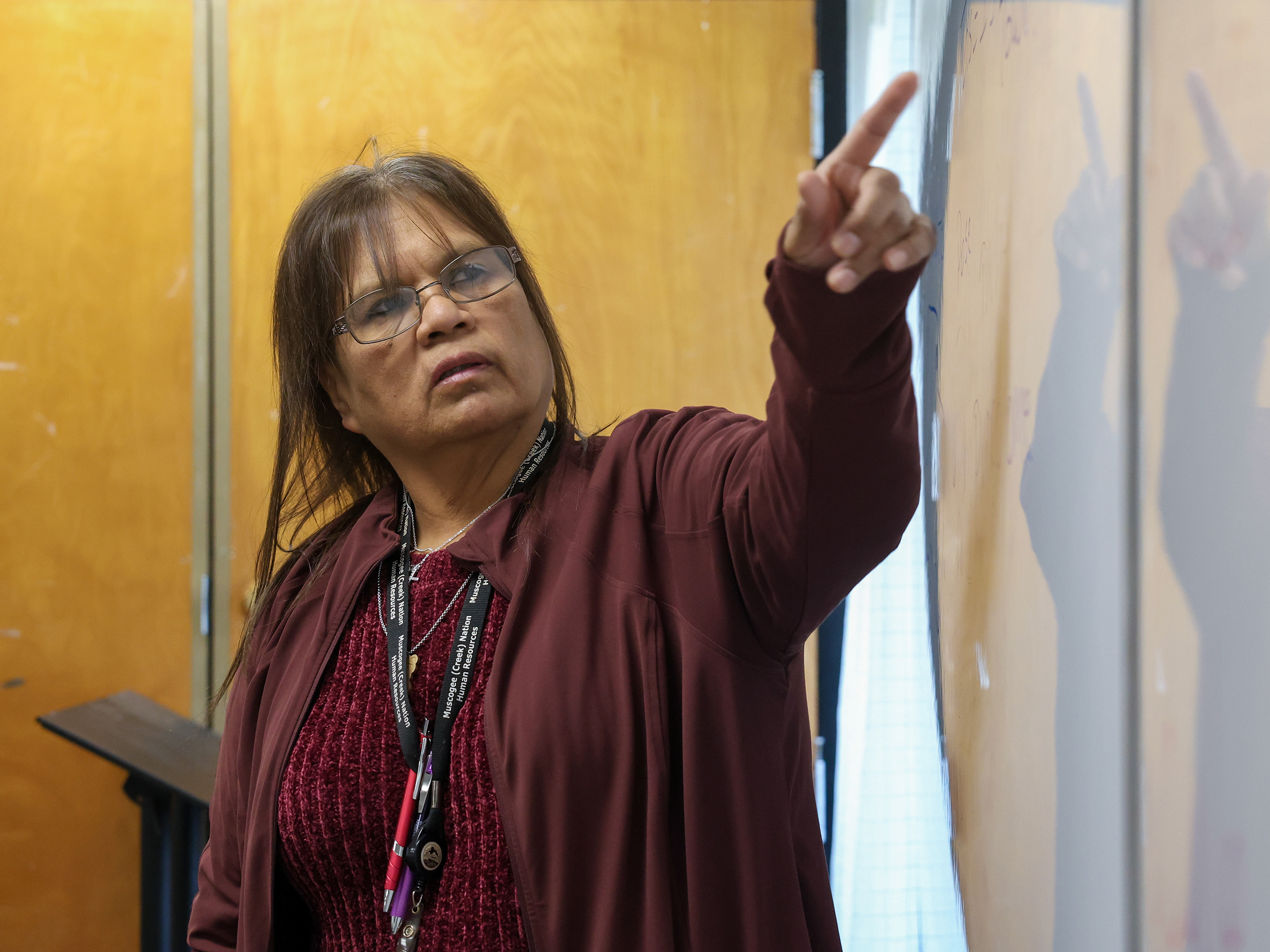

Pearl Thomas is a Muscogee hymn singer and elder at Honey Creek United Methodist Church. Diego Hernandez

As she continued learning Muscogee alongside Cherokee, she began incorporating both languages into her performances, which combine auto-tuned vocals, sampled rhythms and traditional melodies.

Her live show is part ritual, part concert and part challenge to expectations about what Indigenous music is supposed to sound like.

“People still think of Native Americans as being in the past,” Harkins said. “Like we are in museums or history books. But music brings us into the present and into the future.”

The idea that hymns belong solely to the past is one that both Harkins and Thomas push back against, although in different ways.

Thomas sings with a voice shaped by decades of church gatherings and community singings, a voice that carries the stories of her family and her congregation. Her father and uncles were strong singers, and many of the hymns she sings today were passed directly from their voices to hers.

“I was told by an elder once that if you do not know how to pray, you better learn how to sing,” she said. “So that is what I have been doing all my life.”

She has sung at basketball games, funerals, powwows and school assemblies. At a recent university event, her performance of a Muscogee hymn caused a man who had no prior connection to the language or culture to approach her, “He came up and shook my hand and said, ‘That was beautiful,’” Thomas said. “I did not even know ESPN was there filming it, but people listen. They feel it.”

Increasingly, young people are not only listening but participating. Across Oklahoma, schools in partnership with the Muscogee Nation have begun offering language programs that include hymn singing as part of the curriculum, according to Muscogee Nation.

In some classrooms, even Head Start students learn to greet elders, count and sing simple hymns in Muscogee.

Thomas witnessed this firsthand when her great-granddaughter came home from school and surprised her with a formal Muscogee introduction.

“She could say it better than me,” Thomas said. “I asked where she learned that, and she said it was in her Creek class. I had no idea they were teaching it like that.”

While community programs and school initiatives offer formal pathways to revitalization, music remains the emotional anchor.

Hymns are sung at births, weddings, deaths and Sunday services. They are passed around at kitchen tables and sung while driving down back roads. They are what people turn to in grief and celebration.

“The language holds a different way of seeing the world,” Harkins said. “Even our calendar had 13 months once, to reflect the moon cycles. The way we describe the seasons, the way we name the months, it is all different. It is all encoded in the language.”