Muscogee Artist Paints Reality of the Muscogee People

By Elena Andra Stoica

By Elena Andra Stoica

Diacon holding three small paintings of bigfoot, a deer, and a medicine man. He only paints on small canvases so that his community and other people can afford to buy his artwork as most of his artwork is large scale and expensive. Elena Andra Stoica

TULSA, OK — As a young boy Johnnie Diacon constantly was drawing and reading. But as soon as he would look up at the board or try to watch TV, something seemed different because it all became a blur. It was only until he reached fourth grade during a vision screening at his school, which he flunked, that his teachers were able to catch on to what his parents missed – Diacon needed glasses.

Two or three weeks later when he put on the glasses, Diacon’s whole world changed. After reading the chart perfectly, he laid eyes on the office walls, which were covered in old flat style Native American paintings, and he instantly fell in love with them.

“I would go home and take dad's paints and try to replicate what I saw,” the Muscogee artist said. “This is pre-internet, so I couldn't Google it, and I couldn't look it up or anything. There was no way to find out. So, every year, I was always anxious to go back to the eye doctor so I could see his paintings.”

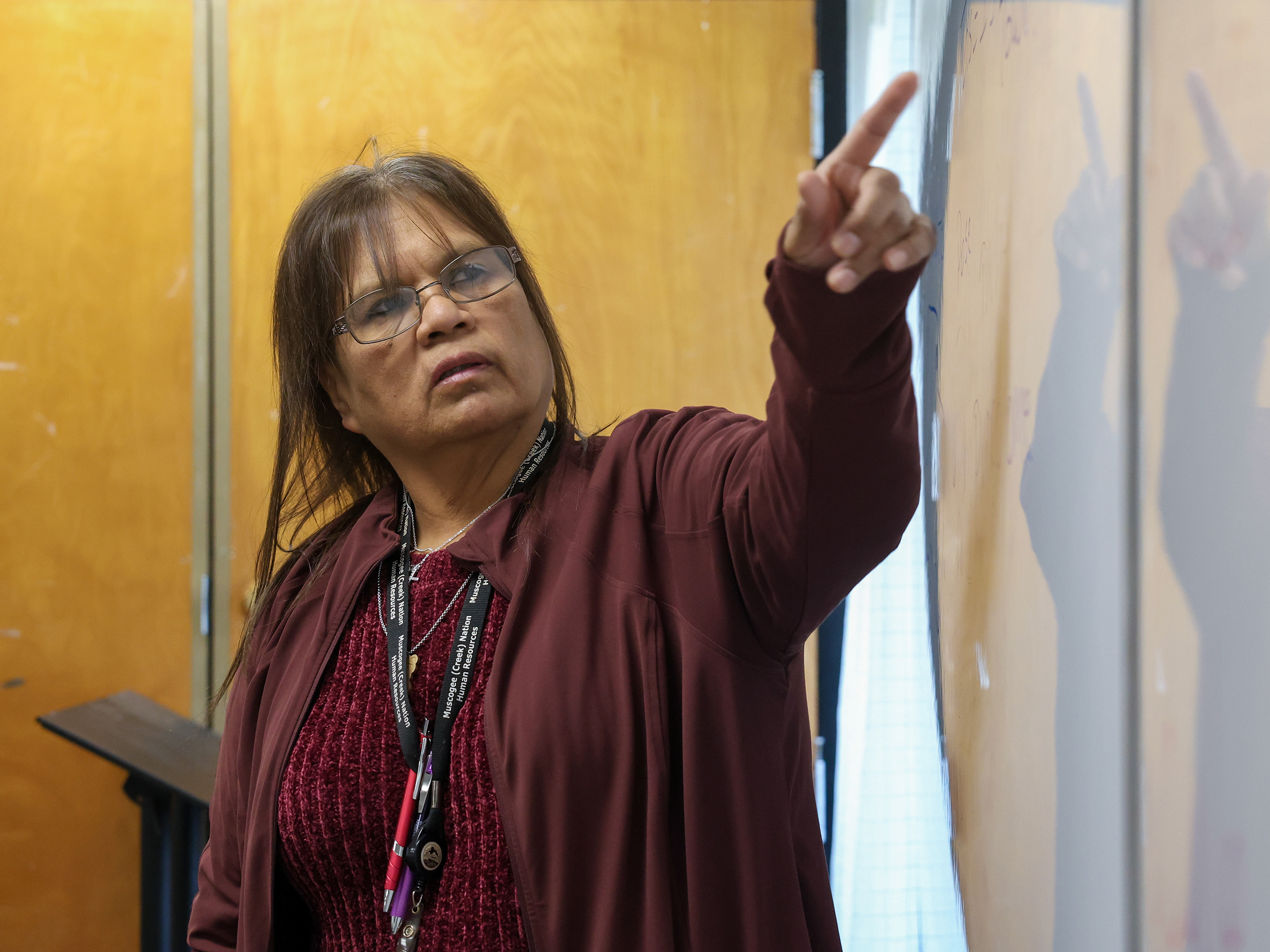

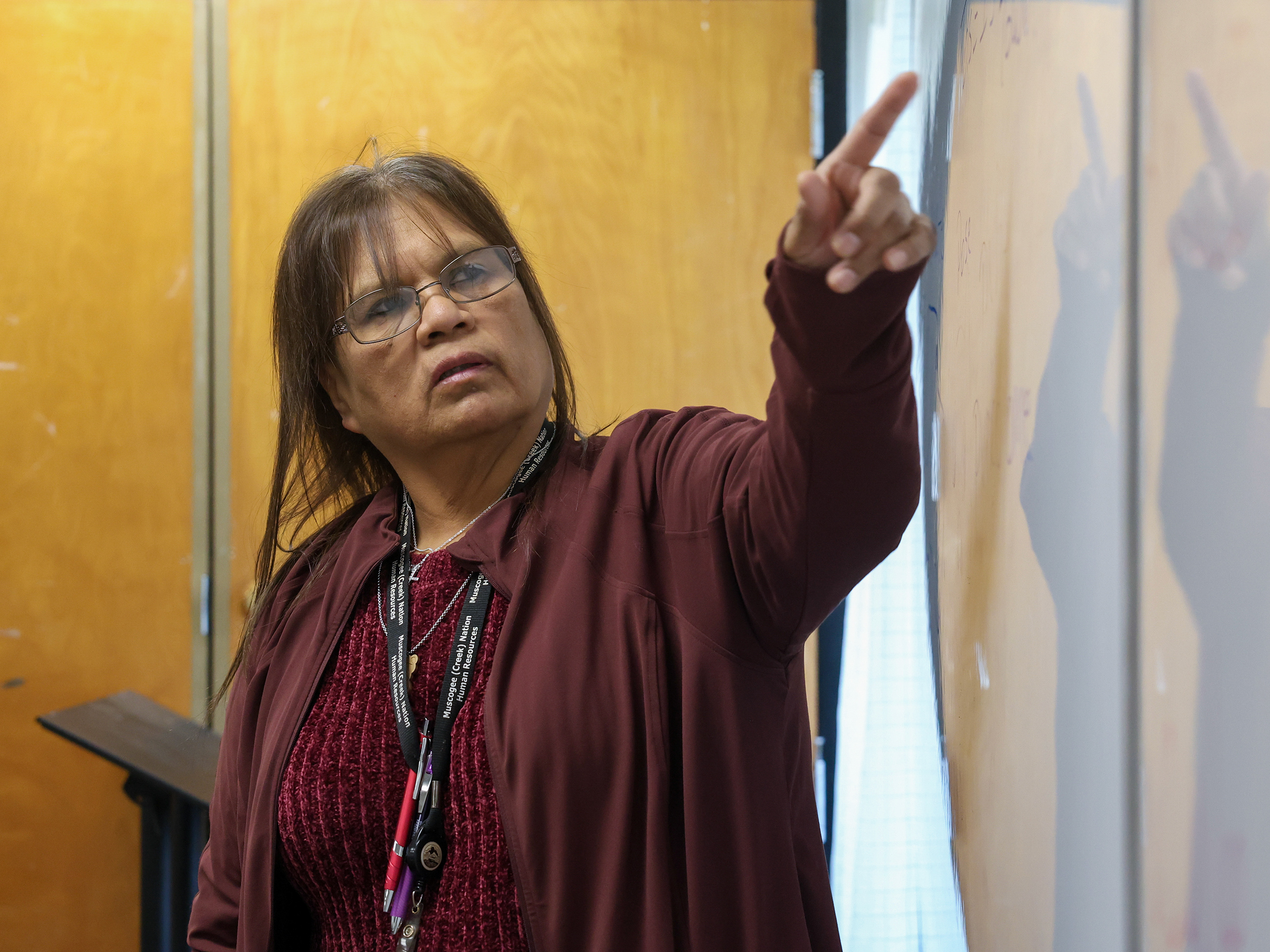

Now 62, Diacon, who is an enrolled member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, has cemented himself as an award-winning artist and one of the few who is in tune with depicting his heritage and people. Based in Tulsa, his art studio has made its own nest in his garage.

Normally, one would expect to find cars in a garage; however, for Diacon, his garage is a sanctuary to his world of art and creativity where time does not exist, and his commissioned paintings do not follow anyone’s deadline. Whether a week passes, and he does not pick up a brush, to a sudden burst of creativity to paint at 5 a.m., Diacon follows his own creative timeline.

At the entrance to the garage, a precise labyrinth navigates around tables filled with paints, brushes, and boxes with artwork prints. An upholstered armchair is covered in a vibrant, colorful blanket with traditional Indian designs and symbols. A couch is filled with huge stacks of paintings. Plastic containers and carboard boxes hold more artwork and supplies that reach the top of the ceiling. One wrong move in this labyrinth, and you could risk a domino effect of disaster. A truly wonderful, organized chaos.

His studio is less a workspace than a living archive, walls layered with framed photographs, colorful tribal patterns, and vintage memorabilia. A half-finished canvas rests on the easel beside him, with deep gradients of midnight purple -- a scene not yet fully painted. Diacon is working on a Trail of Tears painting for the Alabama Native American museum.

Breaking Stereotypes

Growing up, Diacon was surrounded by stereotypes of Native Americans created by Western movie depictions, which show that all Native Americans were Plains Indians living in teepees and riding on horseback. Throughout his life, Diacon had always painted the world he lived in and the world he was part of, and in a way, it became the true representation of what Muscogee peoples’ daily life looks like. Without aiming to break stereotypes, Diacon inadvertently achieved that.

Johnnie Diacon, 62, sitting in his art studio. Elena Andra Stoica

“We are now in charge of how we depict ourselves, how we let the world see who we are, and so that's kind of an important place to be. It’s important, quite a responsibility” Diacon said.

He added this is why it is so important to do his work honestly and accurately, because he believes it is not about him, but his people.

“It's about who I'm representing, and I want them to be seen, and I want them to be seen as who we really are, and so people who don't know, will get to know us,” the artist said.

To combat stereotypes, a collective effort was required from Native Artists, where they had to slowly stop recreating stereotypical artwork, which is popular among non-native Americans, who bought the art which a preconceived idea of what the art ‘should look like’.

Click on the play button below to listen to Johnnie Diacon speak about the impact of non-native art collectors on art creation.

Diacon holding a painting of Muscogee citizens. Elena Andra Stoica

Diacon adds that another layer of protection was the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, which according to the U.S. Department of the Interior makes it “illegal to offer or display for sale, or sell, any art of craft product in a manner that falsely suggests it is Indian produced, an Indian product, or the product of a particular Indian or Indian tribe or Indian arts and crafts organization, resident within the United States.” This law helps preserve representation of Native Americans only to those who are enrolled as part of a tribe, and it protects artists’ work in spaces that are dedicated specifically for Indian artwork.

Diacon said that when he began creating art in the early 1980s, that law didn't exist, and you didn't have to prove that you're enrolled.

“When I first started, I wasn't enrolled with the Muscogee Nation. I was Muscogee, but I was just an Indian.” Diacon only applied to enroll as a citizen once he decided to go to college at age 25 and was told he would qualify for scholarships and grants if he was an enrolled Native citizen.

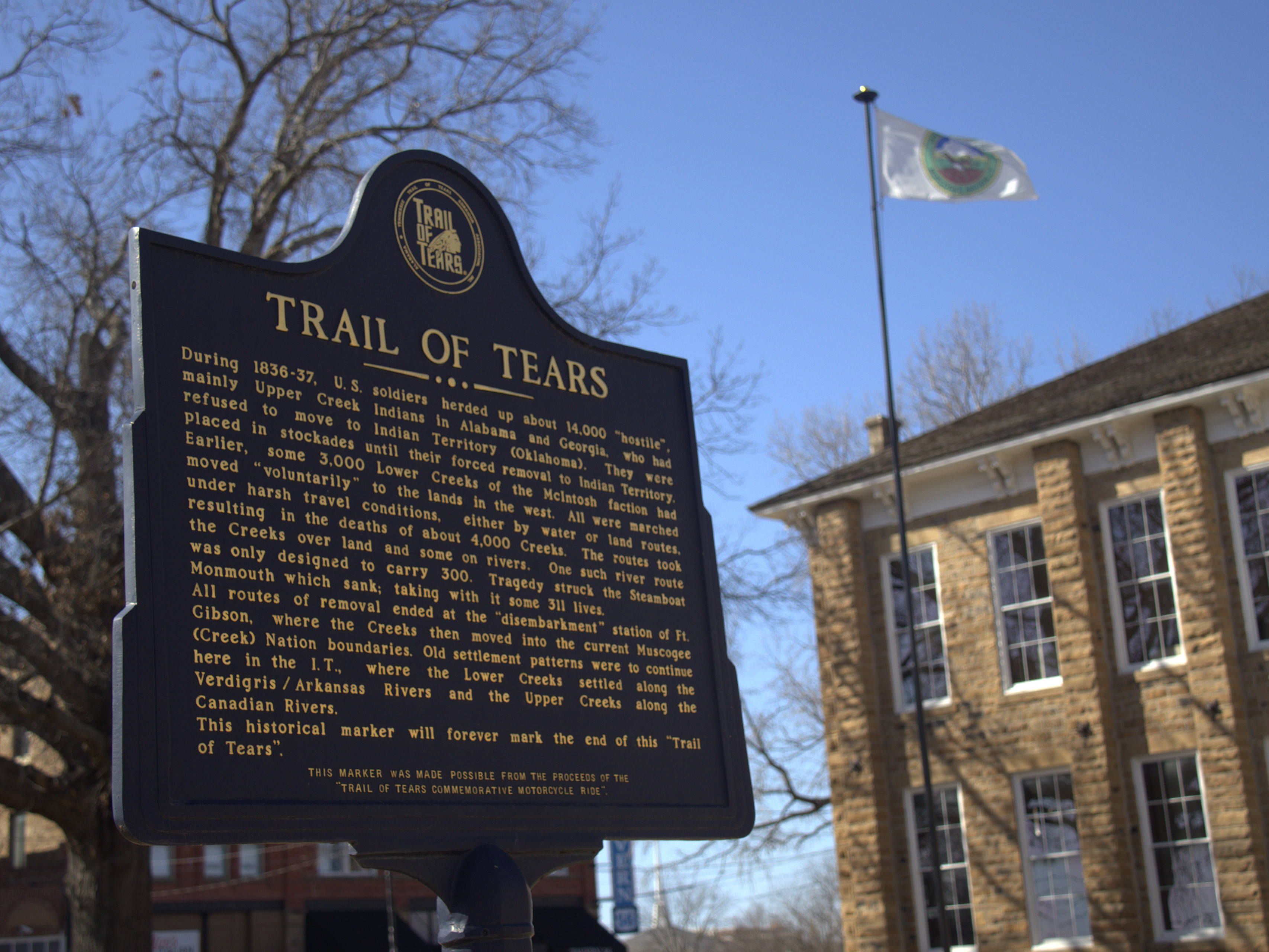

Diacon looking at this unfinished “Trail of Tears” painting for the Alabama Native American History Museum. Elena Andra Stoica

The Trail of Tears is the name of the forced displacement journey of Native American people that took place in the 1830s under extremely harsh conditions, in which approximately 3,500 of the 20,000 Muscogee Nation tribe members did not survive. Diacon describes it as a “death march” and highlights that he does not agree with anyone that romanticizes the tragic and horrible occurrence.

“I don’t like benefiting off my peoples’ suffering, so I do not feel right doing a bunch of Trail of Tears paintings and selling them,” he said.

The few exceptions where he does agree to produce these paintings is in rare occasions such as historical preservation.

Dr. Stacy Pratt, a writer and art collector, describes Diacon’s painting style as one that can capture the true essence of how Creek (Muscogee Nation) people live their daily lives.

“On the internet a lot of people say that they can hear this painting, I can feel this painting, I can smell this painting, and that is how I feel about Johnnie’s artwork because it is so specific to how we live our life as Creek people,” said Pratt.

Dr. Stacy Pratt holding a self-portrait painted by Johnnie Diacon. Diacon was painting a "Trail of Tears" painting for the Native American History Museum in Arkansas. Elena Andra Stoica

Pratt shares that until the show “Reservation Dogs” came out, people did not know how Muscogee people lived and now more people are aware. But at the time when she was seeing Diacon’s paintings, she was thinking “Man you’re really showing all of our secrets, not sacred secrets, but just the secrets of our daily lives.”

That is mainly because a core segment of artwork created by Diacon is focused so minutely on Creek life. A person who is not Creek may think “that it is a cool painting, and they may like that painting, but if you’re Creek you’d think the same and notice the small details that are engrained in daily life,” Pratt said. This is precisely why Diacon’s artwork was selected to be featured in the show “Reservation Dogs,” because it is the type of artwork that not only depicts Muscogee people but also lives on Muscogee peoples’ walls in their homes.

Johnnie Diacon at the Institute of American Indian Arts in 1998. Courtesy of Johnnie Diacon

Painting Past the Pain

Diacon has faced challenging times and at one point did not paint for 14 years. At the time, he had just graduated from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), returning to college in his 30s after years away from school. Once he graduated, opportunities began to open up. Art shows and markets welcomed his work, including the Eiteljorg Museum’s Native art market in Indianapolis.

At the time, his wife was six months pregnant. After she was cleared for travel by her doctor, they made the trip together. But over the weekend, she began experiencing pain. Though her doctor reassured them it was part of a normal pregnancy, things worsened on the drive back home. Once back in Tulsa, her pain became unbearable. By the time they reached the hospital, she was rushed to labor and delivery. She was in labor—had been all weekend—but didn’t know it. The baby, a girl, was born too premature to survive.

“She was only about 10 minutes, she was with us, and she was gone. And it broke my heart, because I thought it's my fault. If I hadn't taken us to that art market while she was pregnant, she'd still be here.”

Click on the play button below to listen to Diacon speak about the two tragedies which made him stop painting for 14 years.

The self-inflicted guilt was so overwhelming that he stopped painting entirely. That loss took the creative spirit out of him. He questioned everything, his art, his success, even his sense of self. He wondered if he was being punished, if perhaps he had grown too full of himself, too focused on achievements.

Years passed.

In 2014, he received a message from IAIA inviting alumni to contribute artwork to celebrate the opening of a new campus building. But he had nothing to show because he hadn’t painted in years.

He didn’t feel ready.

That changed during an event hosted by the Iowa Tribe’s eagle rehabilitation program. There, he saw two injured eagles that were unable to return to the wild, but they still looked majestic. As he looked into their eyes, he felt an unspoken and spiritual message: “We’ve been hurt too, but we’re still eagles. We’re still doing what we’re meant to do—with the help of others who love us.”

That moment stayed with him. Creation, he realized, was the gift he had been given. He was still an artist, even if had been wounded, he still has the love and support from his loved ones. He knew it was time. Picking up the brush again felt natural and like he had never stopped. Since then, he has not put it down.