OKMULGEE, OK — What makes someone Native American ? You might imagine someone from Western movies, a person with long straight black hair, tan skin, riding a horse. The thing about stereotypes is that they are hardly ever true, especially about people.

Angel Ellis, a citizen of the Muscogee Nation in Oklahoma, looks nothing like what the movies have led us to envision Native people. She has blonde hair, blue eyes, and light peach skin. Ellis, head director of Mvskoke Media, has been a journalist for over a decade, uncovering scandals and covering political scandals in her community. With a cigarette in hand, she talked about how to truly understand Native Americans.

“Forget the Western stereotypes and tropes you were absorbed in growing up, and truly come to Indian country with open ears,” she said. “Native America is a modern place, and it's alive and well today and to really see it for what it really is you're gonna have to abandon every notion you had about it.”

The Muscogee Nation spans across 11 counties from Tulsa to Eufaula, having over 87,000 citizens nationwide. Since the adoption of their written constitution in 1867, people from around the country would pass through their reservation and some would stay, starting families and enrolling into the tribe.

In the Muscogee Nation many people are of mixed backgrounds, Latinos, white people, Black people. If you can imagine them in your hometown, they probably live in the Muscogee Nation. To enroll in the Muscogee nation all you need is proof of family heritage. For others it’s blood quantum.

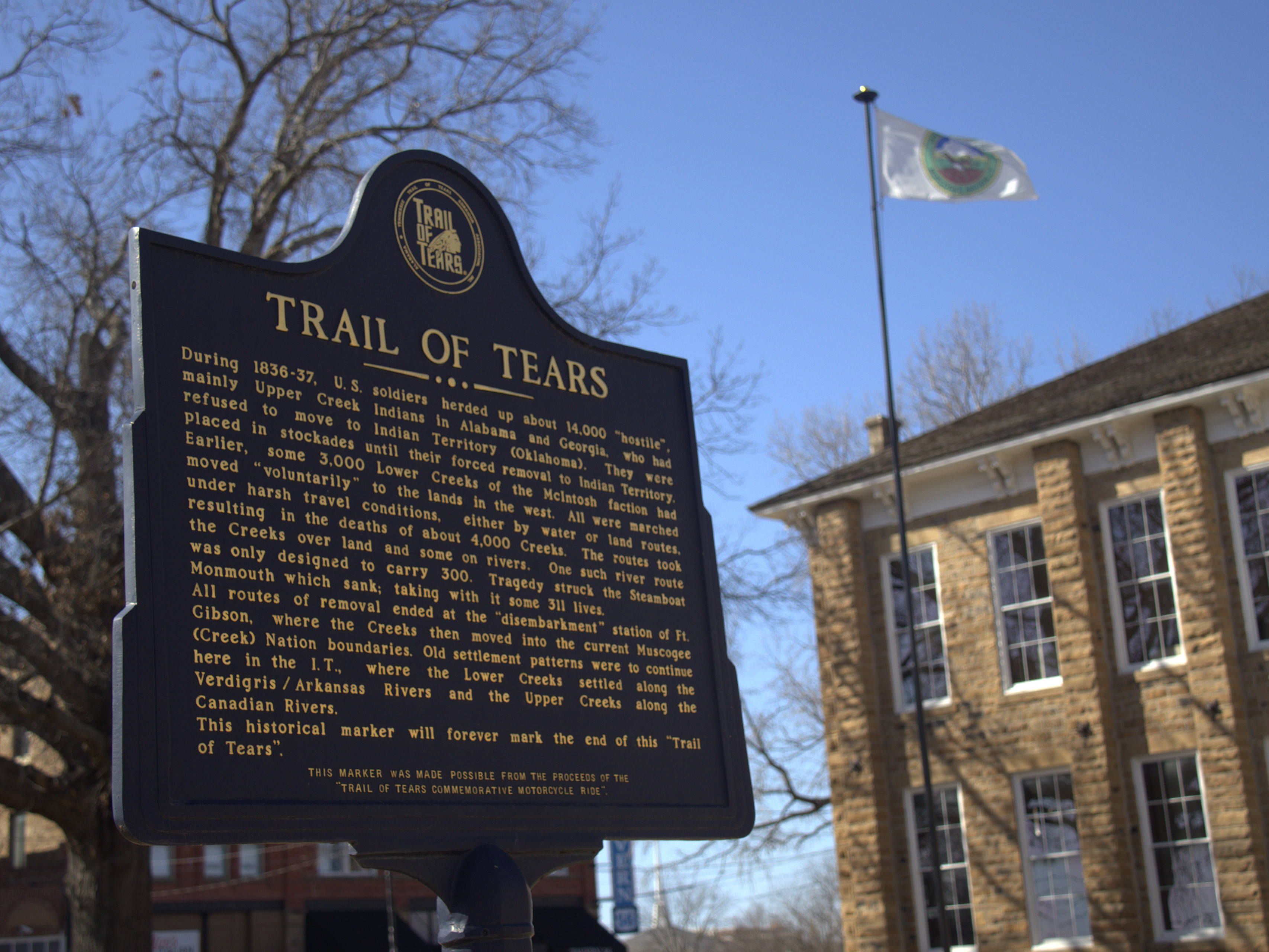

Many tribes in Oklahoma use the Dawes Rolls as a basis for citizenship enrollment.

The Dawes Act of 1893 required natives of the "Five Civilized Tribes": Cherokees, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles to be enrolled in their tribe to receive land allotments from the government. The Dawes Rolls contain the names of over 100,000 natives from 1899-1906, including birth certificates, marriage certificates and court documents.

So in the Cherokee Nation for example the citizenship office would test your blood quantum, specifically to see if you have one-fourth Native American blood. They would also use the Dawes Rolls to look into your genealogy, to see if you have any native relatives.

However, some people are confused about their background, or worse, lie about it, taking the identity of native people and pretending it is their own. Nicknamed “Pretendians,” people who pretend to be Indian are taking much more than just native identity, Ellis said.

Ellis said she wrote a podcast called “Pretendians.”

“I had someone come onto our show and explain this to me. I had a hard time imagining a world where people pretend to be native and scoop up a lot of resources and it’s shit, right?” she said.

Academia is also affected with incidents of professors and students lying about their identity (intentionally or not) to gain some sort of benefit, such as abusing scholarships or building an identity upon a community they are actually not a part of.

“The more prevalent case that you see of “pretendianism” is unfortunately in academia,” said Elizabeth Camacho, a doctoral student of Indigenous political thought at the University of Illinois. “At least once a year an article will come out about oh so and so professor was claiming to be native, it turns out they actually weren’t.”

Pretendians cause problems systematically but also socially, blurring the lines between people with real native relatives, and those with a “Cherokee princess grandmother.” That can also be considered a form of pretendianism, Camacho said.

“Because you're basing your identity on this sort of myth, it's almost like a family legend,” Camacho said. “So that’s what happened to [Senator] Elizabeth Warren, she claimed that she was of Cherokee ancestry. It turns that they (the Cherokee Nation Citizenship Office) checked they Dawes Rolls, and people found out that she had no family on the Dawes Rolls.”

However, other Indigenous scholars don't believe the term has anything to do with looks, but points to a systemic issue.

Robert Smith, is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and a professor of Indigenous history at the University of North Texas. He said he has encountered academics who lied about their heritage, possibly to get funding or prestige. At the same time, he is an Indigenous man who presents as white.

“You know, I don’t think being a ‘Pretendian” has much at all to do with looks,” he said. He defined “Pretendian” as “people who are not enrolled [as tribal citizens] and who have no family lineage or tribal affiliation, but still insist on using tribal identity as a way to validate their work.”

Smith is a tall man with light sand-colored skin. His broad figure, short brown hair and soft but stern face has led people to confuse him for a police officer. However, he is part Chickasaw on his mother’s side, and is an enrolled member of the Chickasaw Nation. He has never needed to lie about his lineage in order to validate his work, as some other s have in the past.

“Those who assume a false identity are damaging to Indigenous people, " Smith said.

“If you do not belong to our community, yet you claim to be a part of our community in order so you can build yourself up, stay away from my people,” he said.